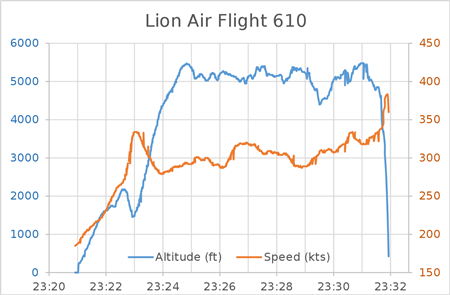

It looks as though the crew on the flight deck of the Lion Air 737Max that crashed, killing all 189 on board, behaved very differently from the crew that flew the same plane successfully the day before.

It looks as though the crew on the flight deck of the Lion Air 737Max that crashed, killing all 189 on board, behaved very differently from the crew that flew the same plane successfully the day before.

The accounts of the final crash report point to a faulty sensor that convinced the plane’s software to force the nose down. The crew on the earlier flight realised what was going on and disabled it by switching the stabiliser trim to “cut out”. The crew of the fatal flight didn’t seem to understand what was happening, and continued to fight against the software and, in the end, the software won.

It sounds as though the first flight crew recognised what was going on, but the second crew didn’t. Their responses were entirely different, with devastating consequences. The first air crew was not deceived by the flashing error signals and shaking control columns, and everyone survived. The crew of flight JT160 misread the signs and fought the symptoms, not the cause.

Deception: real and imaginary

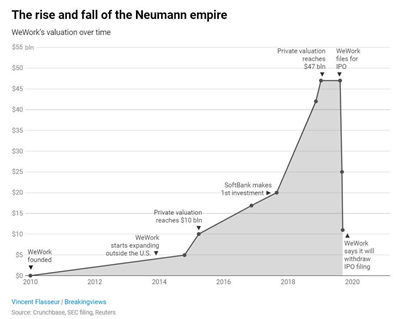

WeWork has crashed too, or at least its plans have. The visionary Adam Neumann drove the Company flat out for scale, aided by billions of Dollars of fuel from Masayoshi Son of SoftBank. It flew high and stalled when the public markets questioned what was going on: more and more properties and growing revenues, but outsiders couldn’t see how it could become profitable – they weren’t deceived by what they saw and acted rationally.

WeWork has crashed too, or at least its plans have. The visionary Adam Neumann drove the Company flat out for scale, aided by billions of Dollars of fuel from Masayoshi Son of SoftBank. It flew high and stalled when the public markets questioned what was going on: more and more properties and growing revenues, but outsiders couldn’t see how it could become profitable – they weren’t deceived by what they saw and acted rationally.

Had Newmann deceived Masayoshi Son, or himself; were they both deceived or were they trying to deceive others? Goodness knows, but plenty of capital was destroyed in the crazy flightpath it took. The new flight crew are now desperately fighting the nosedive, hoping that they can pull up before it hits the ground.

Even now, after the new team has drastically cut back growth and slashed costs, questions remain about the fundamental air worthiness of the thing and whether it can ever achieve sustained, profitable flight. At least the Boeing 737max appears to be an air frame that does fly – ironically, the problems seem to be caused by the safety systems.

The lesson seem to be clear

It pays to look behind the immediate indicators to work out what’s really going on. If you’re already on board, like the first air crew, then knowing what’s really going on can mean survival when big problems arise. If you’re offered a ride, like the public investors in WeWork in the run-up to the abandoned IPO, it pays to look behind the first impressions presented in the prospectus and question whether its safe to climb aboard.

The challenge for investors and Management teams in today’s world is that there’s so much going on and everything’s happening at speed. Pilots today have to guard against what’s called “cognitive overload”, where they get swamped by stuff and can’t cope. Perhaps this is what defeated the crew of JT160 from Jakarta?

Simple indicators versus the reality of technology

Technology businesses today are rarely understandable through simple metrics like monthly sales or gross margin, and this is a danger for Management on the flight deck, and for shareholders joining the flight and those already on it. There’s just too much going on, too many moving parts, and you have to understand the whole picture or your decisions could be completely wrong.

Back in the day, technology was a product that people bought or didn’t, like cars or cakes – each purchase produced some income, and that was that. Subscription models based on usage, hybrid models and platforms interconnecting with different services, put paid to that simplicity. Today’s on-line world means that many forces are at play at the same time, and you have to know what’s going on. I daresay that these factors apply elsewhere, but they are particularly prevalent in tech.

Revenue drivers are a case in point

Revenue drivers are a case in point

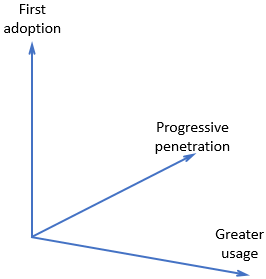

To illustrate my point, a simple income line can deceive so easily – it’s often too crude a measure to be informative – it can hide what’s really going on with the things that drive the revenue. Three main axes usually combine to drive those numbers:

- First adoption – A new paying customer is to be applauded, but most tech companies now have on-going income from existing customers as well as payments from new ones.

- Progressive penetration – Customer payments will increase as the technology or service finds its way across the organisation into new departments, use on new projects and in different ways.

- Greater usage – Customers grow, they do more, they employ more people, their usage grows naturally, or you hope it does. Data grows too – whoever heard of people having less data?

Each of these metrics can be influenced by other factors, too. Adoption rates can be different in different sectors and regions, even though the technology is the same. Penetration rates will differ between customer organisations, driven by all sorts of factors like structure and culture. Usage can be dependent on what’s happening outside the customer you’ve sold to, such as another service yours is dependent on or integrated with, what’s happening in the customer’s marketplace, and so on.

Who’s flying this thing and do they know what’s really going on?

Who’s flying this thing and do they know what’s really going on?

It doesn’t pay to simplify the way you look at a complex business, and technology businesses are more and more complex as time goes on. Composite numbers, year to year comparisons, arbitrary year ends – all can hide what’s actually going on and lead to mistaken conclusions. Revenues might be down at one moment in a booming business, and up in one that’s failing. Nowadays, you have to find out because all those obvious things that are staring you in the face might very well not be what they seem.

It was all so much simpler in the days of up-front payments for perpetual licences, even with annual support and maintenance fees. Not so now. Physical products are going the same way. All the indications are that there will be little ownership of cars by drivers in the years ahead, and trucks are already there. Artificial intelligence opens up another Pandora’s Box.

It makes it hard to test revenue models in the planning stage because there are so many variables. Goodness knows how much power Amazon needs to throw into its analytics in order to understand AWS revenues, and outsiders struggle to see what’s going on behind the few metrics that are released.

The flight trajectory of JT160 and WeWork’s valuation history are slightly different, but the final stage looks eerily similar.

Also:

Blog Pre-flight checks for business

Blog These conditions require skillful driving

Blog Make Believe Startups

Blog Are we nearly there yet?

Blog The future began a while ago

Blog Can entrepreneurialism be taught?

Blog Human engagement is a big opportunity

Blog The Good, The Bad, and The Surreptitious

and

|

|

Peter is chairman of Flexiion and has a number of other business interests. (c) 2019, Peter Osborn