Anyone with responsibilities for the future must look past the chaos and wreckage of Covid-19 and largely ignore anything in the rear view mirror. There will be lots of debate and argument about what happened and how different it should have been, but decision-makers have to avoid that distraction because their focus must be on what happens next.

In this changed world, some areas of change are extreme, yet there are certainties to draw on to give a framework for making decisions about what lies ahead and how to craft the future of the organisations we’re responsible for.

There’s no way back for some

I chatted to Colin Marshall, once, at the time of the first Gulf War. He was CEO of British Airways and we were sat across the aisle from one another on the fast ‘plane to New York. He said “You have to do special things when your revenues drop by 40% in a week”. He was right, and as a CEO myself, I knew what it was like to grapple with cashflow shocks, although not on that scale.

I chatted to Colin Marshall, once, at the time of the first Gulf War. He was CEO of British Airways and we were sat across the aisle from one another on the fast ‘plane to New York. He said “You have to do special things when your revenues drop by 40% in a week”. He was right, and as a CEO myself, I knew what it was like to grapple with cashflow shocks, although not on that scale.

CEOs in many industries in May 2020 would now think 40% was a bit leisurely. Travel, leisure and hospitality have seen income halt, not shrink. Other sectors have seen similar scales of disruption to cashflow as people have stopped being close to one another in personal settings and the workplace, by state instruction or personal choice.

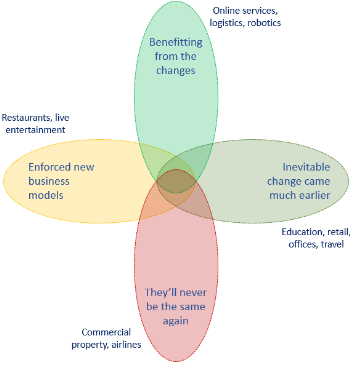

It’s not been all negative. A small Plexiglass fabricator that made display units for museums and high end retail is swamped with waves of business from the sectors most affected by social distancing for screens of all kinds. That CEO is struggling to up-scale fast enough. Anyone in pick-pack-and-ship, and delivery, is facing a boom of equally extreme scale. Technologies that automate and ease the need for face to face interactions are seeing the trends of three to five years truncated to a matter of weeks. Healthcare has undergone a transformation.

No doubt some may see the extreme highs and lows fade over time. Travel will restart, as will physical shopping, leisure and entertainment, but for many, it’s not going to be the same as 2019 any time soon, and the gulf between here and there will be a war of productivity campaigns and business models battles.

The most challenged sectors must find ways of reinventing themselves to survive and have a change to thrive in a world where customer densities are radically lower, and staffing is too. Airlines will shrink and prices rise. How a nightclub or sporting event can operate is hard see see. Football could be televised in empty venues, perhaps, and would suffer, but a nightclub online is unlikely to be much of a revenue generator. Some sectors that were already challenged, now have to think radically. Theatres, opera and many restaurant formats are no longer just marginal – they are not viable.

This isn’t a recession; those are times when everything is largely the same but slower. This is different for large sections of the economy and business worlds. There is no way back for some, and for many it’ll be a scramble to change enough and fast enough.

Plus ça change?

Attitudes are not the same as before, and value systems have changed. The ways that people react and make decisions are different, be they consumers, people on our teams, decision-makers in the other organisations we deal with as partners, suppliers and customers.

Attitudes are not the same as before, and value systems have changed. The ways that people react and make decisions are different, be they consumers, people on our teams, decision-makers in the other organisations we deal with as partners, suppliers and customers.

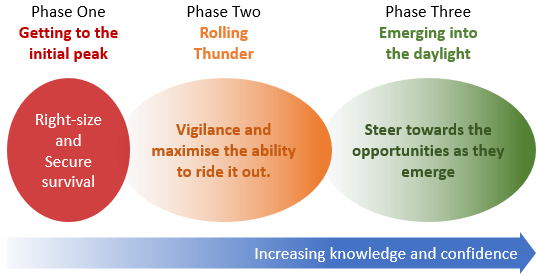

You can see the way business leaders have responded, starting with raw survival and then looking further as their confidence has improved. Not surprisingly, the near-death experience has changed attitudes, and companies are hoarding huge amounts of cash, even as those less fortunate are haemorrhaging eye-watering streams on their lifeblood. US airlines are said to be bleeding over $10bn cash a month with only about four more weeks of runway. This changes attitudes for those watching as well as for those in the middle of it all.

An illuminating study was done just recently into the spending decisions of Scandinavians, and strong similarities were found between the attitudes of those in Denmark and Sweden, despite the very different approach to the handling of the pandemic. The tight lockdown in Denmark and the open and relaxed approach of the Swedish government has turned out to have surprisingly little impact on the behaviour of their populations.

All this serves simply to reinforce the human nature that’s driving decision-making. The more that changes the more we act in inevitable ways. Decision-makers have to decide how those changed attitudes are changing again, and how they will affect what happens around them as the future unfolds.

There have been plenty of pundits talking about the radical change in attutudes that lies ahead, but most of these are those that were arguing for that radical change before all this happened, which makes their punditry look self-serving rather than insightful. Likewise, promoters and beneficiaries of different technologies and product innovations have been quick to argue for the emergence of a brave new world that looks like vindication.

More likely, perhaps, is that human nature will triumph. Whatever happens, decision-makers cannot rely on the attitudes of a past that is long gone. Change has happened, and changed attitudes are the result. Change is still happening and those attitudes will change too. Calling the relevant attitudes correctly will require skill and insight.

No easy financial hangover cure

No easy financial hangover cure

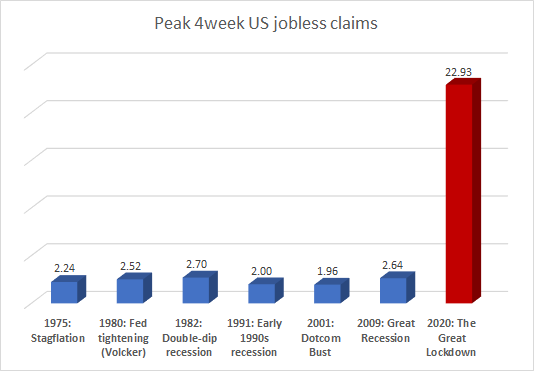

Alongside the wreckage in the business world is a large swath of personal economic woe of breathtaking proportions, and it dwarfs all that’s gone before in living memory. In Britain, the taxpayer is now directly supporting 25% of the workforce in private, non-public purse organisations. This is not going to be fixed anytime soon, and will have so badly damaged so many people directly and affected others, that it represents a certainty that decision-makers will do well to build into their deliberations.

No doubt many of those made jobless will be re-absorbed in time, but it will take time. No doubt, too, many of the those furloughed will be back in their roles and earning full salary, once again. Both will take time, and neither will be a one hundred percent return to what was. At a personal level, this will affect the spending power and wilingness of a very large proportion of the population of previously happy consumers.

So too public debt. Across the five years of the Second World War the UK raised £21bn of debt at today’s prices. By comparison, the Government announced in April that it would raise $180bn in the twelve weeks from May to July, “…in anticipation of its borrowing requirements”. The UK made its final repayment of WWII debt after sixty years in December 2006.

The one key certainty is uncertainty

So many books and column inches were written about the rapidity of change in recent times, mostly expressed around the impact of new technologies and innovations. That’s as nothing against the structural change that’s taken place in the nine weeks since I decided on March 2 to halt face to face business meetings.

Flexibility and choice are now the key attributes of organisations best able to survive and thrive. Decision-makers’ most far reaching impact lies here in their conclusions about the assumptions for the future and what commitments to make.

Whatever the future does turn out to be, it won’t be like the past for many, most even, and the journey from the start of 2020 is destined to have predictable unpredictability, particularly in timing. The decision-maker has it all to play for.

Peter is chairman of Flexiion and has a number of other business interests. (c) 2019, Peter Osborn