Josiah Wedgewood had a lot to do with it. Within four years of starting in 1759, he’d begun to get orders from royalty and the aristocracy, and was one of the first to use celebrity endorsements to power sales to the growing middle classes. He was able to industrialise the production of pottery through his obsession with the chemistry and process of producing ceramics. He was a craftsman potter with other craftsmen around him, but he mastered how to make repeatable designs and scale up while maintaining quality.

Much of the next two centuries were all about industrialising: scaling up production and distribution, and getting more product to ever bigger audiences of customers. Sears began a hundred years after Wedgewood, by launching one of the first mail oder catalogues, aimed at the growing number of people in the American West. This push to get more consumers to buy more things was still the primary focus by the time the Mad Men of Madison Avenue strutted their stuff in the 1960s.

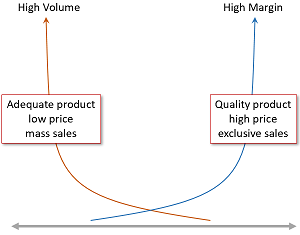

Since the Second World War, though, there has been a growing split between volume markets that have bought on price, and descerning customers who’ve bought on quality, exclusivity and service. Almost all maturing categories have split in two like this: watches, apparel, even airline seats; all these sectors have their low price, cut-down offers, and their high price products and services that are positioned as high quality, personalised, rather exclusive offerings. As time has passed, the two have got separated further and further apart.

Since the Second World War, though, there has been a growing split between volume markets that have bought on price, and descerning customers who’ve bought on quality, exclusivity and service. Almost all maturing categories have split in two like this: watches, apparel, even airline seats; all these sectors have their low price, cut-down offers, and their high price products and services that are positioned as high quality, personalised, rather exclusive offerings. As time has passed, the two have got separated further and further apart.

This led to what became called the “Bankruptcy Bucket” – that ghastly space in between, where you had the problems of both, and the advantages of neither. Think most of the UK car industry: no volume sellers and little cachet, apart from a few outliers. In the end, all those attempting volume gave up the struggle and fell away to one fate or another. A few niche and luxury brands have survived, but hardly any that are independent.

There are signs that this long journey has actually begun a third stage that calls into question the propositions that have justified the high margins. Until recently, individualised products have been possible only with small production runs or bespoke, tailored products, but 3D printing is set to change all that. The time was when personalised service came only at a price, but AI in all its forms in eCommerce and bots brings this within reach at low cost and at scale. Even personal shopping advice is getting mechanised by UK start-up Hero. Much of this effort has been forced on Retail by Amazon and on-line sales, in general. They have shown what excellence of delivery time and service is possible, at scale and at low prices, and the consumer is hooked.

Or are they? Not all are, perhaps. The last five years have seen growing traction in artisan business. Micro beweries are now a widespread phenomenon. Small distilleries are producing an amazing array of craft gins, including ones like the Rhubard Crumble Gin, from Solway Spirits. There are craft bakers, like Forge Bakehouse in Sheffield, where Martha and her team are what draws in the customers, as much as the pastries.

Or are they? Not all are, perhaps. The last five years have seen growing traction in artisan business. Micro beweries are now a widespread phenomenon. Small distilleries are producing an amazing array of craft gins, including ones like the Rhubard Crumble Gin, from Solway Spirits. There are craft bakers, like Forge Bakehouse in Sheffield, where Martha and her team are what draws in the customers, as much as the pastries.

Have we reached the peak of wholesale industrialisation? Not yet, but we’re approaching it. Will there be a backlash caused by the creeping and creepy penetration of that synthetic interaction that comes from automated bots and machine sincerity? I think that’s already here. As mechanisation grips everything around us, will the human become the ultimate business proposition? Will the business world bifurcate once again, but this time into the mechanical and the human?

Also:

Blog Why The Big Short was about entrepreneurs

Blog Selling up is a capital idea if you’re Tarzan

and Interesting Reading

Peter is chairman of Flexiion and has a number of other business interests.